Oct 2006

At first glance, there is little to distinguish Barrouallie on St Vincent's west coast from hundreds of other Caribbean fishing villages.

Small wooden boats lie across the dark volcanic sand. A carpenter saws, goats wander, a radio plays; it's a traditional beach strip unvisited by the million-dollar tourist trade.

Only a series of wooden frames set up along the beach and a couple of huge upside-down iron bowls hint that Barrouallie's fishermen hunt more than tuna and kingfish. The special catch is the pilot whale, known locally as blackfish.

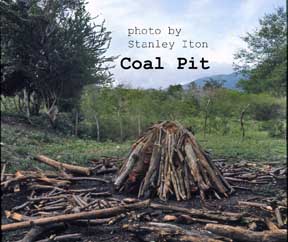

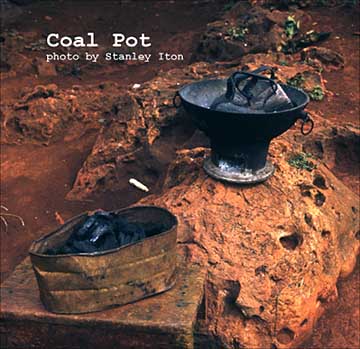

The wooden frames are for hanging carcasses out to dry before processing; the iron mounds were once set out in the sunshine and draped with slices of meat, using solar heat to melt and drain the blubber.

Samuel Hazelwood, owner of one of four or five blackfish boats in the village, tells me how they hunt.

"What we normally do is we have a licence for a 12-gauge shotgun, and we have to modify them ourselves," he tells me.

"We build a harpoon; we take out the pellets from the shot and only use the powder.

"We have the rope attached to the harpoon, and when we go out and see the whales we normally fire the gun and shoot them."

Mr Hazelwood can sell a carcass for about 3,000 East Caribbean Dollars - in the region of 1,000 US dollars. Sometimes, he catches dolphins too; it is a good living, and he is in no mood to give it up.

Ocean bounty

Near the capital Kingstown I find a very different way of using St Vincent's local cetaceans.

Over the last 20 years, Hallam Daize has slowly built up his company SeaBreeze into a whale-watching concern; not yet regular enough to provide a full income, but getting better all the time, he tells me.

Blubber is drained by leaving carcasses out in the Sun

"You see a lot of dolphins; we have at least 10 different types of dolphins. You won't see all on any one day but there's a good chance of seeing quite a few different types, and there are also pilot whales, sperm whales, sometimes dwarf sperm whales and pygmy sperm whales.

"We've had pods of about 17 sperm whales already, and that's pretty remarkable to have them coming so close to your boat."

Like many small Caribbean states, St Vincent and the Grenadines has seen income from its traditional banana crop fall in recent years, blown away by the forces of hurricanes and the World Trade Organization.

There is a huge and unknown bycatch of many small cetacean species in fishing gear around the world

Greg Donovan, IWC

Ecotourism would seem a likely replacement; but is there not a contradiction here? Is it feasible to lure Westerners with images of dolphins and whales gambolling free in nature's seas, while a few kilometres up the coast they are being hunted with homemade harpoons?

St Vincent's whaling commissioner Edwin Snagg, who is also a government minister, sees no problem.

"We treasure our lovely island and we think that we have a very beautiful ecotourism destination and we have a lot to offer," he tells me.

"Whale-watching has not really been a major source of income here. It's an industry which is in its infancy, and we feel that there could be some coexistence - maybe whale-watching and the taking of some pilot whales can all go hand in hand."

Numbers game

Senator Snagg believes that managing St Vincent's pilot whales is a matter for St Vincent alone.

And so far his wish holds true; the International Whaling Commission (IWC), which is holding its annual meeting in St Kitts, has no power to regulate any of the "small cetaceans" such as dolphins, pilot whales and porpoises, despite the belief of its head of science Greg Donovan that some are in serious decline.

Hallam Daize believes there is a big future for whale-watching

"In general," he says, "I would say that small cetaceans are probably more at risk than large whales.

"The difficulty is we have very little knowledge for quite a lot of them in terms of abundance, but also population structure.

"Direct hunting in some cases is a problem but there is a huge and unknown bycatch of many small cetacean species in fishing gear around the world."

Anti-whaling nations and conservation groups have tried hard to strengthen the IWC's remit on small cetaceans beyond the advice which it dispenses now.

But the pro-whaling bloc, led by Japan, wants small cetaceans off the agenda entirely; a position supported by Edwin Snagg, for whom blackfish are a necessary food rather than a cute creature to be protected by Western conservationists.

"It's a question of sustainable use of your resources," he says.

"Here in the Caribbean as a whole we rely a lot on marine life for food, whether it be fish, lobsters, the small pilot whale; and maybe one day someone might get up and say that they'll put a face on a lobster and tell us it's unethical to catch such a thing."

Cold logic

As a major aid donor, Japan clearly has influence in St Vincent.

In Barrouallie, I came across a Japanese volunteer, Mariko Sakuma, working inside the air-conditioned office of a small, cold-storage facility for blackfish built with Japanese money.

When I arrived she was busy drawing up the constitution for a local fisheries cooperative.

Japan has also paid for a room next door where blackfish can be processed according to international standards of food hygiene.

Japan's Mariko Sakuma helps out in the blackfish trade

More details

To Samuel Hazelwood, this is not about buying influence; it is about giving practical and much needed support in troubled economic times.

If nations like Australia, New Zealand and the UK want to see the blackfish trade end, he says, they too should provide support rather than just lecturing on ethics.

"History tells us that America, Germany, Australia, England and those places were the ones who started whaling," he says.

"They can live without catching whales now; but we have nothing else to do. And if you stop us now, just think of the many who are going to suffer because there's no alternative."

Hal Daize sees the long-term alternative as an expansion of whale-watching, which he believes will bring a brighter future for the pilot whales themselves and for the local economy.

"If you think of catching a whale, it's here and it's gone," he says.

"It's like eating a meal; no matter how tasty it is today, by tomorrow it's another meal you need to eat.

"If you go whale-watching, it's like having a tree; you take a fruit this year, next year you get another fruit."

So far, though, the lure of meat today is proving more attractive than the promise of fruit tomorrow; and Hal Daize agrees that if Western nations or conservation groups want a transition, it is up to them to help manage it